Prof. Glaucio Aranha

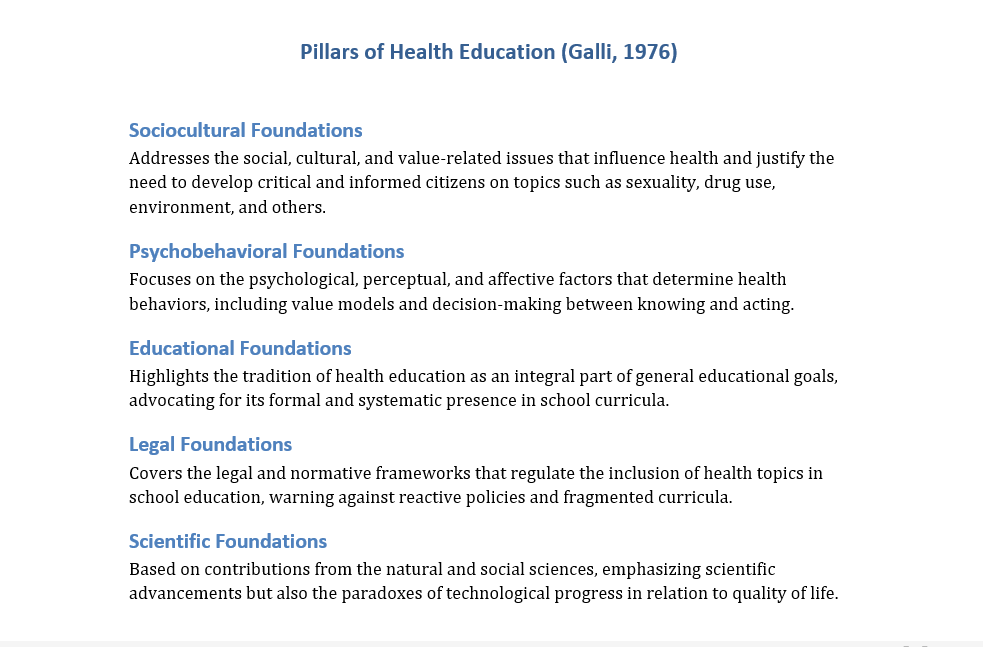

In 1976, educator Nicholas Galli published a seminal article in the Journal of School Health titled Foundations of Health Education, in which he proposed a structuring model for the field of health education, organized around five foundational pillars that guide both practice and research: (1) sociocultural, (2) psychobehavioral, (3) educational, (4) legal, and (5) scientific. Nearly half a century later, the text remains surprisingly relevant — not only due to its clarity in recognizing the complexity of the field, but above all for anticipating dilemmas that have since deepened in a society marked by pandemics, environmental collapse, infodemia, and profound technocultural transformations.

Galli’s model is, in essence, an attempt to bring organic coherence to a field that is necessarily inter- and transdisciplinary. It begins with the realization that health education cannot be limited to the transmission of biomedical information; rather, it must integrate scientific knowledge, social values, affective dimensions, and pedagogical practices that are deeply contextualized.

Sociocultural Pillar

The sociocultural pillar of health education, as outlined by Galli (1976), is based on the premise that health is simultaneously a biological condition and a phenomenon largely shaped by values, norms, beliefs, and social practices. In this sense, attitudes toward the body, illness, care, and prevention are molded by specific historical and cultural contexts. For instance, while in some cultures bodily exposure during medical examinations may be perceived as natural or even desirable, in others it may cause discomfort or be morally condemned. Similarly, eating habits, conceptions of sexuality, or even the definition of what is considered “healthy” vary deeply across social groups and must be taken into account in educational strategies.

In pedagogical practice, this foundation requires health educators to become both cultural mediators and semiotic interpreters. When addressing topics such as vaccination, contraception, or nutrition, it is essential to acknowledge and respect the symbolic repertoire of the individuals involved. It is not enough to correct their “misinformation” with scientific facts. For example, a campaign promoting healthy eating in traditional communities must consider local food practices and their affective and ritual meanings, otherwise it risks being perceived as colonialist or authoritarian. Thus, socioculturally situated health education approaches the realm of listening, dialogue, and the shared construction of meaning — a path also suggested by Lotman (1996) in his understanding of education as translation between cultural languages.

The convergence between Galli’s thinking and Lotman’s cultural semiotics (Lotman, 1996, 1990) becomes evident in the understanding that every educational process is a process of meaning-making. Consequently, health education must operate across the symbolic borders of often conflicting value systems — between science and belief, between the biological body and the lived body, between public policy and community practice. In times of fake news and ideological polarization, this dimension becomes all the more urgent and complex.

Psycho-behavioral Pillar

The second pillar in Galli’s model — the psycho-behavioral foundations — highlights the importance of understanding decision-making processes and the subjective mechanisms that influence health practices. Galli had already warned, drawing from the earlier work of Suchman (1963) and Horn & Waingrow (1965), that knowing what is “right” does not guarantee right action: there is a gap between knowledge and behavior, mediated by values, emotions, context, and symbolic frameworks.

Galli begins with a simple yet profound observation: people do not change their habits just because they know what is right or healthy. Change depends on a combination of subjective, emotional, and social factors — such as personal values, life experiences, family models, and cultural representations. Building on the insights of Suchman (1963) and Horn & Waingrow (1965), Galli (1976) contends that health education must act within this gap between knowing and doing.

To understand this pillar, consider someone who has been smoking for twenty years. They know that smoking is harmful, have read warnings on cigarette packs, and may have seen public health campaigns. Yet, they continue to smoke. Why? Because smoking may be associated with stress relief, emotional memories, or deeply ingrained routines. In such cases, the behavior persists not due to ignorance, but because of psychological mechanisms that must be acknowledged and addressed. The health educator, therefore, must both convey essential knowledge and facilitate processes of reflection, value clarification, and conscious choice — a process Galli describes as value clarification education.

This formative approach demands participatory and learner-centered methodologies. For example, facilitating open discussions with adolescents about sexuality and disease prevention is not about imposing norms, but about helping them identify what they value, fear, and desire for themselves. The aim is for healthy behavior to emerge not from mere obedience to external rules, but from a meaningful, sustained, and reiterated choice. In this context, to educate for health means to form critical and autonomous individuals, capable of making decisions based on a broad understanding of what promotes their well-being — physically, psychologically, and relationally.

Nearly four decades later, this insight presents an even greater challenge: how can we promote meaningful changes in lifestyles in an era of information overload, fragmented attention, and weakened social bonds? The value-based education or value clarification approach proposed by Galli can be updated by incorporating the collective imaginary and media environments as key arenas of semiotic dispute over what constitutes health, well-being, normality, or risk.

Educational Pillar

In the educational field, Galli draws on the North American reformist tradition to demonstrate that health education has long been present in school policy agendas, although often in a peripheral manner. In the twenty-first century, we observe a similar ambiguity: on one hand, there is growing recognition of the importance of mental health, sexuality, and nutrition; on the other hand, ideological resistance, budget cuts, and the lack of robust teacher training in this area still persist.

The third pillar identified by Galli (1976) — the educational foundations — refers to the very tradition of the school as a space for forming healthy, critical, and socially responsible individuals. Since the nineteenth century, thinkers such as Horace Mann, Benjamin Franklin, and Henry Barnard have advocated for the inclusion of health as an essential goal of public education. The reason is simple: without health, there can be no full learning, nor effective participation in social life. Thus, health content has come to be recognized as an integral part of general education, not merely as an occasional addendum.

Nevertheless, Galli warns of a persistent issue: health is often treated as a “cross-cutting theme” which, due to its lack of anchorage in specific disciplines or clear curricular policies, ends up being neglected. In this sense, health education must be understood as a structuring dimension of the school curriculum, with clear pedagogical objectives, specific methodologies, and appropriate teacher training. This requires acknowledging that discussing healthy eating, sexual education, accident prevention, or mental health is not merely a matter for biology class, but a shared responsibility across subject areas, and above all, among schools, families, and communities.

In practice, this foundation invites educators to transform health-related topics into meaningful learning experiences. One example would be addressing personal hygiene with elementary school children not only as a set of behavioral prescriptions, but also as an opportunity to discuss self-esteem, social interaction, and respect for the body. For adolescents, topics such as mental health and substance use may be explored through interdisciplinary projects that integrate language, science, and the arts. In other words, the school must be envisioned as a space for holistic development, where the promotion of health is intertwined with the ethical, emotional, and cognitive formation of students.

Legal Pillar

The fourth pillar in Galli’s (1976) model addresses the legal foundations, emphasizing that health education is a normative requirement in many national contexts. Laws, curriculum guidelines, public policies, and recommendations from international organizations often mandate the inclusion of topics such as disease prevention, sexual education, vaccination, mental health, and healthy eating in schools. These legal instruments serve as regulatory frameworks that grant legitimacy and obligation to health education practices, promoting their institutionalization.

However, Galli warns of the risk that such legal measures may arise solely as reactive responses to crises, which can lead to fragmented curricula, poorly planned programs, and weak pedagogical foundations. A historical example is the introduction of sex education into various Western school systems during the 1970s and 1980s, often prompted by outbreaks of sexually transmitted infections or the rise in teenage pregnancy. The result, in many cases, was the rushed implementation of content without proper teacher training, without dialogue with communities, and, worse, without consideration for local cultural values.

For educators, understanding the legal foundation is essential to act with confidence, legitimacy, and ethical commitment. This means being familiar with existing legal frameworks — such as the rights of children and adolescents, the principles of comprehensive education, and international agreements on health and education — and knowing how to translate these into context-sensitive educational practices. For example, when addressing vaccination in the classroom, a teacher may combine scientific information with the legal rights to health protection, fostering critical and civic discussions. In this way, the legal dimension becomes a lever for empowering individuals and fostering social transformation through education.

The legal pillar also gains relevance when we consider recent decisions by Brazilian states regarding issues such as sexual education, mandatory vaccination, and the use of digital technologies in health monitoring. The fragility of integrated public policies reveals that while legal norms are necessary, they are not sufficient to ensure effective, critical, and emancipatory educational practices.

Scientific Pillar

Finally, Galli addresses the fifth pillar, the scientific one, with an almost prophetic clarity in highlighting the paradoxes of progress, since increased longevity has not necessarily translated into improved quality of life. The author had already warned that many technological solutions create new problems — a thesis that resonates directly with the postmodern critique of thinkers such as Baudrillard (1993, 1991) and Lyotard (2021), who question the blind faith in technoscience as the savior of humanity.

This final pillar proposed by Galli (1976) concerns the scientific foundations of health education, emphasizing that the field is supported by evidence generated by the natural and social sciences. However, this does not mean conveying science in an abstract or dogmatic manner, but rather translating complex knowledge into accessible understandings capable of guiding practical and meaningful decisions in everyday life. Health education, therefore, must be informed by science, but must also render science comprehensible, critical, and humanized.

Historically, the evolution of public health has accompanied scientific advances. The discovery of vaccines, the development of antibiotics, the understanding of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, and the role of neurotransmitters in mental health — all of these have radically transformed how we live and care for our bodies. Nevertheless, Galli draws attention to an important point: scientific progress alone does not resolve the dilemmas of contemporary health. On the contrary, many technological innovations pose new ethical, environmental, and social challenges. The automobile, for example, reduced the risks of contagion once associated with public transportation, but has become a symbol of sedentary and polluting lifestyles today.

For health educators, this pillar demands an active stance of constant updating, critical curation of information, and ethical commitment to scientific communication. In the classroom, this may translate into activities that foster students’ scientific literacy — that is, their ability to understand how knowledge is produced, how evidence is validated, and how decisions are made in contexts involving uncertainty and risk. Thus, discussing the limits and possibilities of artificial intelligence in medicine, or reflecting on controversies surrounding medications, diets, and alternative treatments, can be effective ways to work with this pillar. In doing so, science ceases to be a mere collection of facts and becomes understood as a cultural, dynamic, and deeply human process.

Final Considerations

In an age of artificial intelligence in medicine, algorithms that predict diagnoses, and digital platforms mediating care, Galli’s warning is more relevant than ever: health is not only a matter of data — but of meaning.

Revisiting Foundations of Health Education today is an invitation to conceive health education as a complex, plural, situated, and necessarily critical practice. Galli’s model, although dated in some aspects, provides a heuristic structure that can — and should — be updated in light of the social, cultural, and technological transformations of recent decades.

If today we speak of health literacy, ecology of knowledge, care technologies, or sensitive pedagogies, it is because we recognize, as Galli already suggested, that health goes beyond a physical condition — it is a symbolic, relational, and political construction. Therefore, to educate health educators is to train cultural translators capable of inhabiting the borders between science and life, between norm and desire, between technique and affect.

References

BAUDRILLARD, Jean. A ilusão do fim: ou a greve dos acontecimentos. Trad. Paulo Neves. Lisboa: Relógio D’Água, 1993.

BAUDRILLARD, Jean. Simulacros e simulação. Trad. Maria João da Costa Pereira. Lisboa: Relógio D’Água, 1991.

GALLI, N. Foundations of Health Education. Journal of School Health, 46(3), 157-165, 1976. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1976.tb02003.x

HORN, David; WAINGROW, Sylvia. Some dimensions for smoking behavior change. In: Annual meeting of the american public health association, 93., 1965, Chicago. Proceedings… Chicago: APHA, 1965.

LOTMAN, Yuri. Universe of the Mind: A Semiotic Theory of Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

LOTMAN, I. La semiosfera I. Semiótica de la cultura y del texto. Selección y traducción del ruso de Desiderio Navarro. Madrid: Cátedra, 1996. [Colección Frónesis]

LYOTARD, Jean-François. A condição pós-moderna: uma pesquisa sobre o saber. Tradução de Ricardo Corrêa Barbosa. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 2021.

SUCHMAN, Edward A. Sociology and the field of public health. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1963.

Descubra mais sobre Glaucio Aranha

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.